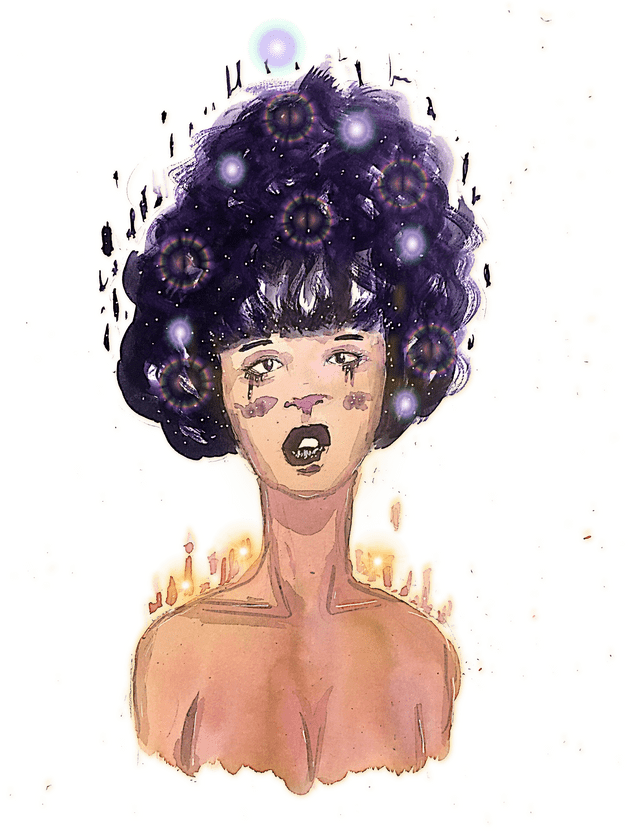

An Interview with Casey Goggin

Interview by Nicole Araya

These two photos are part of your larger photography and poetry journal entitled “Subject/Manifest/Destitute”. Would you like to talk a bit about the photographs and poetry of this project that are not represented in the Women’s Issue? Where does each part take place and how do they factor into the four act American drama described in your artist statement?

Subject/Manifest/Destitute is a photography and poetry journal that was captured over the course of a five-day, meandering drive from San Antonio (TX) to Los Angeles (CA), though of course that drive does not conclude with a physical destination. The 'acts' take place chronologically, one shoot/location a day, from June 6th - June 9th. In order, we stopped at Big Bend National Park in Southwest Texas (June 6th), White Sands National Monument in New Mexico (June 7th), the Apache Trail in Arizona (June 8th), ending the project on Interstate I-15 by the Mojave National Preserve in California (June 9th). With all of these locations, I intended to chase these violent contradictions I saw in them. I suspected that the violence and beauty (thus the contradictions) of these places would parallel, or perhaps contrast, the contradictions I embody in a productive way. Here's an idea of some (not all) of the conflicting pasts and present states of these environments.

-Big Bend National Park is popular tourist and camping site, where American citizens and visitors are invited to gawk at the beautiful Rio Grande flowing between very stark and brutal red mountains. All of the roads leading west, east, and north from the park are bottled up by Border Patrol checkpoints. This area was previously inhabited and accessed by the Chisos, Mescalero, and Comanches native people.

-White Sands National Monument was once inhabited by the Mescalero Apache people. It is a sacred land, the largest deposit of white gypsum crystals on Earth, left behind in the Tularosa Basin by ancient seas. It is also a United States military testing range. In 1945, the first atomic bomb was tested on these lands. When we first tried to enter the park early June 7th, it was closed for missile testing.

-The Apache Trail was inhabited by the Apache Indians. It was formally established under the National Reclamation Act of 1902, and leads to the Theodore Roosevelt Dam. It provided water supply and hydroelectric power to white, American settlements that were pushing West.

-The Mojave Desert is the driest desert in all of North America. It rests between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, places of riches (for some) and vice (at the expense of others).

You mentioned that it is important that the images depict a journey with different locations and scale. Why is it significant that the sequential photos are varied as you described? How do the different settings and distances of the subject from the camera describe the protagonist’s different states of being along their journey?

The varying scales of the photos was an attempt to visually grapple with the relationship between nature and my ego. Before embarking on this trip, I had envisioned photos on various scales just for some variance, but on the road this motive acquired more meaning. I started this project with a lot of thought about myself, my body, my gender, me me me. However, starting with our first day out of the car at Big Bend, these thoughts felt very small, petty, and irrelevant. I had been in nature for long periods of time before, backpacking in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina near where my family lives. Those hikes had felt friendly, and reflective, which is what I suppose I expected of these environments. Instead I found them harsh, cruel, massive in a way that left very little space for my ego or identity. The varying scale quickly became about that relationship. I went on this trip with the intention to grapple with my identity, through artistic exercises and just personally as I drove with my dear friend, Luke. That intention quickly morphed into frustration and despair and hopelessness in the environments we encountered.

The photo taken in White Sands, New Mexico pictures the figure lying in the sand, disrupting the uniformity of the white surrounding. What drew you to the colors that paint the landscape of this photograph?

The promise of the horizon of white sand and the crystal blue skies was just the promise of Utopia. I think that's what really drew me to it, aesthetically. On camera, and in my mind, it's a gorgeous, pristine, breath-taking environment. However, I call it Utopia with the understanding that Utopia - or the strive toward it - will fail. White Sands was actually extremely hot and arid. It is a missile testing range. It is a sacred land that has been stolen. I got a horrible sunburn. If the wind whips up, the gypsum crystals will lash at your exposed skin. It became this gorgeous place I was drawn to and I soon understood I didn't belong there and could die there very quickly.

In the third section of your poem, “Purgatory,” you mention walking barefoot in a land inhabited by rattlesnakes and saguaro needles. In the corresponding image you are pictured at the top of the mountain of the Apache Trail in Arizona. Can you tell us a bit about the experience enduring the terrain to travel up the mountain?

Walking up to that spot and staying there for the duration of the shoot was fairly stressful. I had not walked all the way up to the peak you are referring to actually, until my photographer, Luke Martinez (they/them), asked me to. I hesitated rather forcefully when they asked me to do that. Already I was kind of concerned about stumbling onto some kind of dangerous animal, or even just stepping in the wrong place and getting a leg-full of cactus needles. There was also an element of anticipation in that process though - some kind of punk instinct, I suppose, that welcomes pain. LOL. I am not sure how to describe the conflicting feelings I had, but I was relieved by the end of that shoot. It was the most stressful one.

In your artist statement you mention that the work “is a fiction, insofar as the body is a fiction.” How did you come to the decision to involve the myths of the West in reflecting your social reality?

I guess it was my intention to explicitly involve the myths of the West in my social reality, but it was not necessarily my decision. My dad went into the military after high school, and the training he received - his loyalty to the nation, his conception of manhood - was directly imposed on me growing up. I think that's had a pretty unfathomable impact on my psyche - though of course I cannot begin to imagine his own psyche, and I have sympathy for that even after everything. My family is also white and of Irish origin. The Goggins were brought to America as indentured servants in 1721. They worked on a plantation in Virginia for a century until they, unlike the dehumanized and enslaved black bodies who did this work as well, were permitted to pursue their own 'destiny.' The Goggin family moved West to California at that time. It was sold as a promised land for poor white people. The only reason I did not grow up in California is because my dad joined the military, so we moved around military bases in the Southeast. So in this drive I took, I wanted to grapple with the fictions that were forced upon me: this notion of 'manhood' that is conducive to the military expansion and preservation of America as a nation, this promise of the West for white bodies like my own and like my family's, and the way those stories have been told and retold to me (sometimes by me, in my head) in a way that could only make them fictional, not factual.