Simulacra

Fiction by Disha Trivedi

There is an artist in a loft that should have been gutted a long time ago. It is in the city’s aching heart, but nothing about it resembles the steel-and-stuccoed world outside. The ceiling exposes every pipe. Paint comes off the walls in golden curls, revealing a pigeon-colored undertone. Sunlight takes a different slant inside, slashing across a pantone print on one wall and a faded tapestry on another. Old and new sing together and rattle in the steam that runs through the pipes.

The city’s wind knocks on the windows. The city’s people hardly ever knock on the door. But when they do, the artist takes the visitor to the front room. It is an open space, all floorboards that prick and creak under her ever-bare toes. She offers them a pot of old-brew drink—tea or coffee? do you have the pure shot-after-shot, patch-after-patch caffeine that is so favored nowadays? no, I don’t stock that. She listens to what they ask of her. Most of them comment on the pantone print. A few glance wistfully at the tapestry. All of them commission her.

They never ask her to replace anything too large. One of them wants her to remake a teapot well-loved by his wife; he broke it in the heady rage of arguments and regretted it in the aftermath. Another asks for pet that died and which the parents would like back for their daughter. Once, winsomely, a small city council crowds her creaking living room and asks, winsomely, for an entire garden. Complete with swings and a set of witch hazel trees.

She labors on the witch hazel blossoms, tiny kisses of petals that they are, for weeks. Her hands wear a second skin of clay. She forgets to eat for forty-eight hours.

That is her life. Once she abandons the real world, past and present, she becomes the art.

Food shows up at her doorstep once every three days, the tea and coffee a gift from a fervent admirer with connections in government departments that still stocks such old-world reminders. No one knows where she gets her clothing—simple and clean and airy. Perhaps she makes that as well.

No one knows her name, either. Her works comes unsigned. She is simply the artist in the loft.

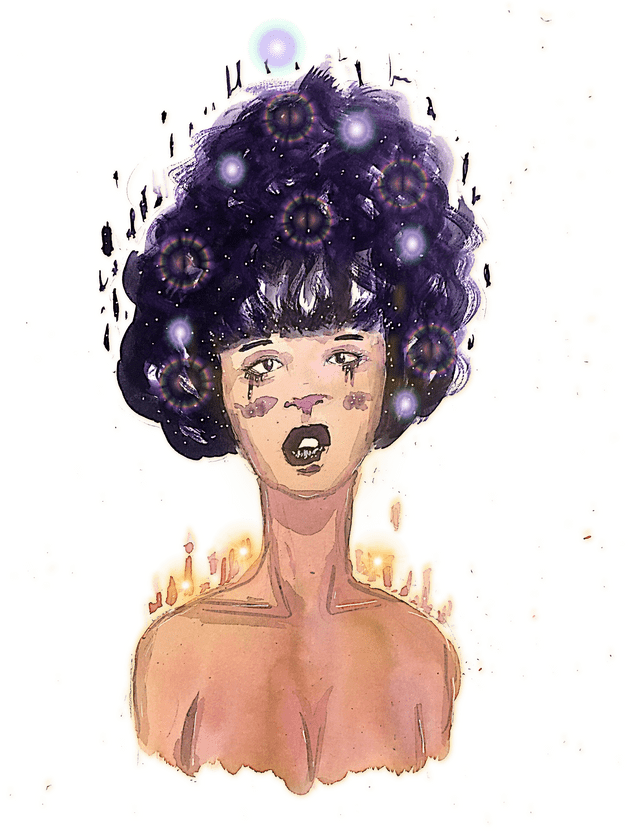

Sometimes, as she leaves the front-room’s façade, she wanders into the space furthest from the entrance. It is full of white-sheeted silhouettes, mannequins, ghosts waiting for her to breathe into them that forbidden life. And it occurs to her that perhaps, she, too, is just something made from clay and spare parts and science: Pygmalion, Prometheus, Frankenstein and his monster. She sits among the clay-and-wire craft of her art, and breathes, and listens to the sounds of the city that has embraced the future, and waits.

She does not know for what.

When it comes, it falls like a shooting star.

James is nervous. His hands shake. Coffee is bitter in his mouth. “My father used to drink this,” he says.

She looks at him. He wants to ask her name again, feels the urge to do so sliding up his throat like bile, but does not. He drains the coffee instead.

“Helen’s been to see you,” he asks at long last. “Hasn’t she?”

Let us step backwards.

It is autumn when Helen Foley comes to the artist in the loft. The first thing to note about her is that she is also an artist. Her words are her paint box. She looks at the well-constructed front room, at the print and the tapestry, and simply nods, as if she had seen the answers she needs and does not want to ask the rest.

She holds herself like a woman who has faced enough to know that she is not invincible but would like to be.

“I want you to make me,” she says.

And now, further back.

Helen Koslov is an artist. She has always been one. Her life is an ink and paper castle. She loved books even when their flesh-and-paper form became abstracted off into the digital ether. Her family had come from an Eastern European nation that has since lost its name in the tides of historic diplomacy and current events and future wars.

As a girl, she knew that words gave her knowledge, and knowledge gave her the childish invincibility that comes from believing that she could become anything she wanted. Even to the point of stripping away an old immigrant name and taking another.

This is how Ileana became Helen. Helen, the ruination of men; Helen, the destroyer of a shining city; Helen, who, despite her uncompromising way of looking at the world, wanted just to be everyone’s beloved.

“Love” came in the form of an unforgiveable angelmonster of a young man, when she had just grown out of girlhood. James Foley was a thinker and a doer, a shaker of worlds to her maker of words, a star shooting across the light-polluted sky. They were introduced when they had both just left the same law school, over a mutual friend’s dinner party that featured too many finger foods and not enough champagne.

At James’ greeting, Helen said nothing, merely smiled her distant smile. In certain small circles, Helen was admired for her sharp-tongued voice of reason. James had been a larger-than-life presence, his circles spanning every cross-section of their world. He had been loved or hated (there was no in-between), but most importantly, he had been known.

The only person by whom Helen wanted to be known was someone she thought she hadn’t met. James Foley, with his grand theories and charismatic tricks, did not particularly illicit any response from her other than mild irritation.

She sipped champagne, bored. But she had constructed her boredom so that it always gave the impression of looking like she was thinking Big Things. A girl with no particularly beautiful features or particularly winsome life story had to make herself attractive somehow. She used her mind.

James, whose rare girlfriends had all left him because he was always off thinking Big Things instead of thinking about them, saw a soulmate.

A soulmate does not have to be someone with whom one wants to spend the rest of one’s life. That is a common misconception. Soulmates can be siblings, best friends, babysitters, cats, even certain inanimate objects with the express power to change humans (a story, a work of art, or even a place). For something to be a soulmate, it must only accomplish the simple and excruciating task of showing your soul to you, in all its light and dark.

Soulmates sing you back to yourself.

James Foley did not know whether to hate Helen Koslov or frantically chase after her. To compromise, he made their mutual friend engage them in conversation. Helen, sharp and territorial, rose to James’ bait.

They saw something in each other, were irritated by it, and walked away as rivals, certainly—and friends: perhaps?

Helen tells this all to the artist in the loft, in between sipping tea.

“Surprise me,” she replies, when the artist in the loft asks her which sort of tea she preferred.

“Chamomile?” she asks upon receiving the cup. Her lipstick leaves a stain on the edge. She wipes it away with a careful finger. Lipstick, she later confesses, was something she had started wearing for James, and for the cameras. It is not easy being a politician’s wife.

The artist in the loft listens. She will need all the stories she can get to work with the clay. Crafting a soulmate requires knowing the soul.

James and Helen should never have ended up friends. James kept placing himself into her story, weighing its pages down like a paperweight.

He wanted her company at cluttered old museums that nobody else visited. While getting lost in community gardens and surreptitiously tasting strawberries from someone else’s vines. In cemeteries, peering at the graves of poets from centuries past. He wanted her thoughts on civil service reform, on the new airborne highway system, on the energy crisis. He wanted to see her art. And she wanted, eventually, to share it.

She fell in love with him first. She couldn’t tell exactly when. She woke up one day with that feeling lying next to her, not knowing how it happened. That was how love worked itself into a life.

He wanted to give her his mind, not his heart. She set about how to best make him give her both.

In the loft, the artist looks at their pictures: the mayor and his wife at the modern art museum’s annual ball, at the state’s new energy plan signing, at the revamping of free digital education access for children in non-wired neighborhoods.

Helen gives the artist all the pictures that they have in digital form. Their projections coat the walls of the artist’s loft. Now, it is hard to imagine James and Helen as anything but a unit, inseparable.

Then come the clandestine pictures, the ones saved on glossy paper instead of pixelated mist, the ones that Helen had taken when James wasn’t paying attention, when the press wasn’t watching or before he was important enough for them to care.

James in a bookstore, his back against the shelves, paging through a copy of The Iliad back when bookstores were something that still existed. On the beach, his hands sunk in the sand. At a birthday, surrounded by the blurred shades of other people caught moving around him. In a room before a circular window overlooking a snow-frosted tree, face a grayscale painting, horribly uncertain, stripped bare.

The artist looks at the last for a moment longer.

Wind shifts through the sheets that she had thrown atop her automatons, her Frankensteins, her simulacra. She looks up, startled. Perhaps one moved.

“I want you to observe us in person,” Helen says. She was not one to take no for an answer.

“What is your story?” Helen asks after a long silence, after a series of no’s had been sung.

The two women look at each other for a long time. Honesty creeps up and sits between them, as it had since Helen laid her life bare in a way that journalists would snatch up, if the artist ever spoke of it.

She won’t. Helen implicitly trusts the recluse of a woman who won’t let modernity to sneak up on her and bite her shoulders and scratch her eyes.

Helen trusts her because the artist’s face is full of words lurking beneath the surface. Words unspoken when one only has walls and statues to talk to. Secrets that have been kept for a lifetime.

Helen had heard of an artist who could duplicate the dead and copy the living from—James. James, who wondered whether it was borderline illegal or immoral to use tech made for resurrections, weighed the situation and decided to let it pass. The artist could have her art. She was capable of raising Lazarus but asked for no gospels in her name. An enigma: intriguing, forgotten.

Helen, curious, investigated.

Helen found the artist and saw a soulmate. At the very least, a soul who had seen similar worlds, who knew what it was to walk away.

The artist was once small and young and an immigrant. Her birth city embraced tech in a way that her current home, with its stuccos over the steel, had not yet. This birth city had been cold and cutting and utterly home, for a while. She grew.

She was much like Helen, in that she once had a sharp tongue and wise mind. At first, she made art that she showed and shouted to the world. Then came the first man in her gallery to look at not the art, but her.

“What is in that head of yours,” he asked, “that makes you dream up the nightmares that everyone wants to see?”

He kept searching her for the answer, and she kept trying to give it to him. When it did not come, he crushed her like a brittle leaf in the wind. Tore her art to the ground, splintering and splattering it like bodies when he did not like it. Took it when he did. Leaving her hollow, nameless.

She came to a new city empty, waiting to be filled with dreams again. Because she did not like this new city that she had moved to after leaving behind her childhood nation, she wandered very little from home. Less and less, in fact, until she did not wander at all.

“I’m not sure if I should be doing this,” the artist confesses. Those words have been hugging her, haunting her. Making pets and gardens and once-whole teapots as replacements were one thing entirely. They blurred the edges of good and gray, but this was another task.

She does not like that they live in an era where not all technologies encourage creation instead of control, where not all city-states are kind instead of cruel. Artists in her world are locked up, mouths taped, left with prison cells for canvases. She is not that kind. She does not like choosing sides.

“Men,” Helen says after a long instance, “have ruined us both.”

“Elaine,” is the name that Helen gives her at last, when the artist refuses to yield up her real one. Even as the mayor’s wife, Helen refuses to abuse her power and search up her records.

Why?

“Your tapestry.” Helen pointed to the weaving on the artist’s wall. “Did you choose it because of the legend of the lady of Shallot?”

Helen is too well-read for her own happiness. Her shelves are full of tragedies. Elaine visits her when James is away. Helen does not want Elaine-the-artist-in-the-loft to be seen by her husband.

Elaine shivers a little, because Helen purposefully keeps the house a little too cold. Even with heat, it is too large a place for a woman who stays in one room to write and a man who stays outside to move and shake the world.

“Can I ask—” Elaine is hesitant. “Why don’t you have children?”

Helen smiles, humorless.

To everyone else, Helen and James are a universe unto themselves. Moving together, in tandem. I would say more, but all the comparisons have already been made, and besides, I am not Helen: There is a limit to my way with words.

They are all three at one of those events. One where anyone is small enough to be anonymous and visible enough to be noticed, depending on their preference. Elaine finds the former easy.

The artist waits. She notes how James and Helen are a separate sphere in the game of press and politics: no one encroaches upon the space around them.

She catches when Helen’s smile freezes, and James gently tries to tug her on toward the next journalist. When Helen does not answer the question that a reporter asks, and James, with a laugh designed to be winsome, redeems the moment.

But what will they say to each other, later, alone?

How did James Foley and Helen Koslov end up rising in the ranks together, owning the city and each other, their souls tied up in knots?

Simple: they let each other. Neither of them knew how to fall in love, so neither of them knew how to not fall in love. They were each other’s first loves, and therefore, they concluded, their great loves. Everyone who is anyone must have a great love, especially among the smart and famous and fierce. Sarte and Beauvoir. John Adams and Abigail. Dali and Kahlo. Mary and Percy Bysshe.

They fit the other’s notion of the one true, the perfect other, the storybook ending, the chapter in the unwritten autobiography.

Love doesn’t work like that. Helen, the first to fall in love, was also the first to see that truth.

“I gave him too much.”

Helen had been visiting for some weeks now. Elaine opens up enough to let Helen to stand among the sheet-covered statues.

Helen removes one sheet and stares at a face still unmarked. A blank space where there should be human features. Her mouth tightens in surprise, but she does not replace the sheet. “Some people think this technology is blasphemous.”

“Have you ever believed in God?” Elaine asks.

“I do.” Helen closes her eyes.

“I gave him too much.” She gave him an earful and her heart, her mind and her worldview. She gave him the support that he had needed when the press started to eat at him, when he had failed, when he was in the dark before his slow climb back into the starlight. She gave him her life, eventually.

She was her own woman with her own words, and he had always respected that, and yet the world relegated her to the subordinate title of “the mayor’s wife”—

Stop pushing me, James.

No.

I’m not going with you; I’m tired. I’m allowed to be tired.

Sadness is not something I can will away.

Will you please listen to me instead of interrupting me?

He was such a force. The air in the room belonged to him when he spoke. Nobody breathed until he was done. She was the one closest. It was tiring to be family and best friend, wife and confidante, soulmate, soulmate, soulmate.

She wanted air.

It happens. Two months after Elaine the artist got her pseudonym from the mayor’s wife, the same mayor’s wife winds up in the hospital, ill, comatose, found collapsed in her home.

Elaine, not one to often use the technology laced subtly into her life, ventures outside. She watches one of the news projections plastered on the steel-and-stucco streets. The tired-eyed mayor stalks out of the hospital and past the press and makes it to his car, where she supposes he might allow himself a rare moment of weakness.

Perhaps.

The artist crafts. The face, once blank, becomes smooth, planed. Cheekbones like mountains, nostrils like crevasses, a cavern for a mouth. A face so often seen laughing besides James in the press photographs. A face that Elaine got used to having in her home. A friend.

Even technology like this requires an artist’s hands.

The mayor’s wife wakes two days later. The stories leaked by nurses say that when the mayor came to her, he took her hands and put his face in them and cried. Helen had told Elaine that James had cried once or twice in her entire time with him. He was good at willing sadness away, especially sadness of the public sort.

Helen had looked at him for a moment, blank-faced, the nurses say, like she couldn’t remember where she was. And for a moment, everyone held their breath because she had stolen all the air from the room.

Then she smiled, and said his name, and James learned to breathe again.

So does Elaine. She breathes. Guilt-ridden, accomplished, relieved.

What was the mayor’s wife thinking in that moment? Let me tell you.

She had woken with her mind intact and full of memories that somehow felt like a movie she had watched instead of one where she had the starring role. Her hands were soft, unblemished, since some of the details of a person cannot be fully captured—not the scar she’d gotten in France when, slicing a squash, she’d cut open one finger; not the calluses from her recent rock-climbing trip in what remained of the Canadian wilds. But she knew, somehow, that those details should be there. She had the memories.

No artist is perfect.

But I, the one who emerged in that bed, the one into whose hands the mayor cried, was the perfect Helen. That is my only flaw.

“Helen’s been to see you?” James would ask later, shakily, to the artist-who-was-not-really-called-Elaine.

Elaine’s fractional response before saying, “Yes,” was long enough for James to put his head in his own hands this time.

James, the shooting star, whose pictures always showed his wife at his side. His infallible other half.

He lifted his head, and his face was tearless.

This is the story: Seven years ago, Helen Foley, tired, discovered that she was carrying her husband’s child. In silence, she chose not to have it, because it came at a time when James was in the midst of political havoc, and because she wasn’t sure that either of them was ready.

Years later, it is with cold eyes that she realizes that Helen Koslov—smart, uncompromising, surefire girl that she was—would not have made that choice.

It is the little things that come after, the moments when she submits to James’ greater will out of greater love, that shows her that she loves him too much. More than herself. Helen the girl, smart and strong enough to rival James, could have stayed merely that—a rival, or at best, a friend.

Helen the woman does not tell him about the child they never had, just as she does not tell him of her plan to leave him so neatly that James Foley never has to be apart from her, the one person who was his match.

This is the story that I steal from the artist in halting words, when I come asking for answers. This is the story that I live with, the birth of who I am.

I am the second half of what could have been the story of two people whose love was not enough. The replacement.

I was made to be Helen enough to replace the real Helen for James, to never realize that I am not the real Helen at all. But I, I am Helen too much. Do I choose as she chose, as the artist in the loft chose: to walk away?

And where is she?

Helen is chasing herself again. She has her own story to tell. Just as I, now, for better or worse, have mine.