The Evolution of My Brother

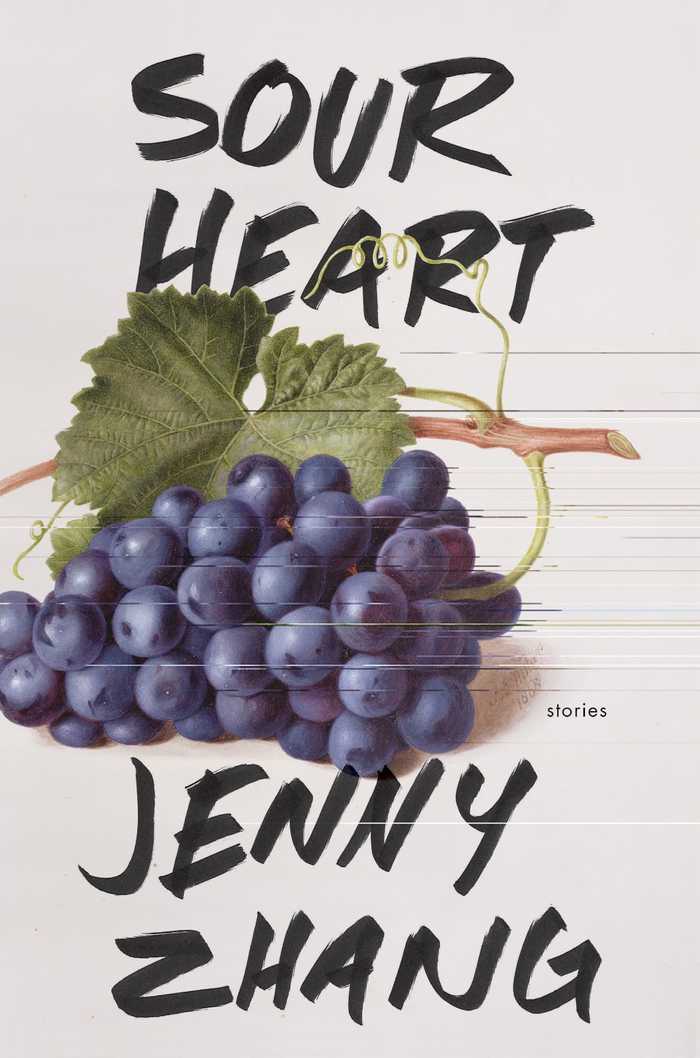

Fiction by Jenny Zhang

I.

We were alone most afternoons. On one of them, we searched my room for candles. We found one that I liked: white with Colombian coffee beans clustered around the bottom.

“Eat it,” I said.

“No,” my brother said, furrowing his eyebrows, turning away.

“Eat it, eat it, eat it, eat it, eat it.” I backed him into a corner with the coffee end of the candle pointed at his mouth.

“Stop it, Jen-naay,” he said, stepping back, “or I’ll enable my force shield to turn your bones into dirt.”

“Okay, fine. Let’s light this and then blow it out. Let’s do it like twenty times in a row. It’ll be just like our birthday.” “Why twenty? That’s too many.”

“Fine, twenty-eight it is.”

“No. That’s more than twenty.”

“Okay, okay, fine. Fifty-five, if you insist.”

We set the candle on our living room coffee table. I told him to stand back while I lit up the match and touched it to the wick. “You first.”

He crouched down on the ground, closed his eyes, and leaned in close. Neither of us expected the front of his overgrown bowl cut to touch the flame, to curl up immediately, to change color as if he had gotten a badly bleached body wave. If he were old enough, I would have laughed and said, “Cute pubes.” But instead, I covered his face with my hands and pulled out the burnt ends. The little crisps disappeared between my fingers when I rubbed them together. It smelled just like popcorn.

“Let’s not tell Mom.”

“Okay, Jenny.”

I picked out the rest of the burnt strands, and the two of us ate them from my cupped hand while we sat on the couch, my arm around him and his feet wiggling like noodles in boiling water, our eyes staring straight ahead, as if the opening credits were coming on.

The next summer, I pulled him inside my room and locked the door. I was supposed to be teaching him addition, but I tossed the workbook on the floor and stuck a pair of headphones on his head.

“Good thing your head’s so big.”

I turned the volume up. He was five and starting kindergarten in three weeks. I was going to be a high schooler.

“So the casbah is like a huge palace,” I said. When he started to get that distracted look on his face, I turned up the volume another few dials and told him to pay attention. “This is important,” I said. “When kids on the bus ask what you’re listening to, you just say: PUNK ROCK MOTHERFUCKER!” I folded all his fingers down into his palm except for his fore- finger and pinky.

“What?” he shouted. I pushed one of the headphones away from his ear and held him by the shoulders.

“Look at me.” We stared at each other. “You’re listening to punk rock music, the most rockin’ music ever made in this extremely unrocked-out world. So you just listen to this on the bus and school the shit out of the other kids about rocking out.”

“Why?”

“You’re a punk rocker now.”

“Can you make me cereal with milk?” he asked, handing me the headphones.

He came in holding two pieces of ham stuck together and wearing a Mickey Mouse sweatshirt over a hand-me-down turtleneck that was so old and stretched out on him it reminded me of our neighbor’s Dalmatian after he was neutered and had to wear a big plastic cone around his neck. I had said so the last time my brother wore it. (We were outside throwing sticks for our neighbor’s Dalmatian to catch and my brother asked me what neutering was and I said, “Hold on, I’ll get some scissors and show you,” which earned me an appalled look from our neighbor, and I was immediately embarrassed because I knew he found me odious and cruel.)

I felt bad whenever I saw my brother wearing my old turtlenecks and when I saw him eating food supplied by our mother. Our mother had a habit of shaping food into hard tangerines. She’d cram his mouth so full of food that I’d find him sitting on a couch, dazed and unable to close his mouth or swallow. I’d pick him up and carry him to the bathroom so he could spit everything out into the toilet. I pitied him because I knew he would never have an easy relationship with food, not now and not when he was older either.

“Please stop feeding him,” I said to my mother once.

“You must be kidding,” she said. “You were the one who begged me for an extra five dollars a month to feed African babies.”

I was reading a magazine when my brother walked in, his mouth overflowing with half-chewed ham, and instead of taking the two slices of ham away and showing him the proper way to eat and instead of re-cuffing his drooping turtleneck so it didn’t look quite so pathetic, I ignored him and pretended I only cared about the new sweater-skirt combos for autumn. When he wouldn’t leave, I told him, “You have to.”

“No.” He folded a slice of ham into his mouth. “No, I don’t.”

I nudged his shoulder. “Yes, you do,” I said, bumping the other slice of ham out of his hands.

“Hey,” he said, butting his head against my stomach. We started using knuckles, fingernails, pillows, magazines. He kicked my leg, and I struck his cheek, the ham side. His mouth opened, and big fat tears slid down his cheeks and into his open ham mouth.

Seeing him like that made me feel like a monster. “Spit it out,” I begged.

It would be my fault later in his life when he wouldn’t take packed ham and cheese sandwiches to school, and even later, when his teacher made a phone call to our mother, concerned that he had refused to eat the ham sandwiches the cafeteria had prepared for the annual seventh-grade overnight trip to Boston. It was my fault. It had always been my fault. It would be my fault again in the future; it was endless. “Please,” I whispered. More pieces of chewed-up ham slid out of his mouth. He tried sucking some of them back up in between gaspy breaths. I cupped my hands together and offered them to him. “Just spit it out in here.” The ball of ham in his mouth seemed to be expanding from the addition of all his tears. “I can’t see you like this.”

Later that day, when we were getting ready for bed, I showed my brother how to pull back his lips to look at his gums, and when he did, I found a little piece of uneaten ham stuck between his incisors.

“Can I have it?” I asked.

“Why?” He smiled wide, baring his teeth so I could pick the piece of ham out. I popped it into my mouth. It tasted so, so salty.

He had a temporary stutter where he would add the sound “ma” to the beginning of certain words. Sometimes, when he called out for me, he would say, “ma-ma-ma-ma Jenny.” It sounded like he was saying, “my-my-my-myyy Jenneeeeeeee.” I liked being his property.

“It’s very common,” the speech pathologist told us. “It’s a tic, almost like clearing your throat compulsively before speaking.”

“Is it significant that he often does it before saying my name?” I asked, hopeful.

“Not particularly,” the speech pathologist answered.

“She’s a quack,” I said to my parents when we got home. “I don’t believe a word she says.” I went and found my brother pacing around in circles in the TV room, taking great care to keep the speed at which he paced perfectly steady. “Say it again.”

“What?” my brother asked, continuing to circle until I stood in front of him, blocking his path.

“Say, ‘my Jenneeeeeeee.’ ”

“My Jenneeeeee,” he said, pushing me away and continuing to circle.

“No. Say it like you did the other day. Ma-ma-ma-myy Jenneeee.”

“Ma-ma-ma-myy Jenneeee,” he repeated after me, completing another perfect circle.

It wasn’t the same. He was growing up. He was growing out of his speech disorder. From that point on, in order to be his, I had to request it.

When I was fifteen, I spent three weeks in California studying philosophy at Stanford University with people who made me feel like I was part of a tribe—their tribe, not mine, but a tribe nonetheless. All I had wanted for so long was to be part of a family that wasn’t mine. To have an excuse to love mine less, an excuse to run away instead of staying so close all the time. “Why,” I wailed to our parents the week I got back, “do we have to do everything together? Why can’t you ever go someplace without us?” My brother was standing as close to me as he could without touching me. I had warned him that if I felt any part of his body touch mine I would saw it off. “Why does it always have to be the four of us? Do you really think I’m going to live here forever? Maybe he will,” I said, pointing at my brother, “but not me.”

“You should have stayed in California, then,” my mother said.

“If you want to stay home while we go to Home Depot, that’s no problem,” my father said. “It’s fine. We’ll take your brother with us.”

“Jenny’s not coming?” my brother asked. “If you come one inch closer to me, I swear to God,” I said. In the weeks leading up to my Stanford trip, everyone had been extremely tense. I was about to experience my first taste of independence and I wanted to celebrate, but my excite- ment had been deflated by my mother’s moping, my brother’s tears, and my father’s absence—he seemed to be staying late at work even more than usual. Everything became an argument—whether I was going to check one bag or two, whether I should buy a phone card now or wait until I got to California, whether I should try to find used copies of the as- signed books or buy them new at the Stanford bookstore. The one thing we didn’t ever bring up was money, how I had convinced my parents to spend nearly six months’ salary to get me to California and cover tuition and room and board, how I had sold them on the necessity of all of this. I wasn’t thinking about how the first time either of them had ever traveled anywhere significant was to America from Shanghai, with nothing more than eight boiled eggs in their pockets, fifty dollars that were confiscated at customs upon arrival, and a suitcase full of pots and pans and one broken broomstick for fear that they would not be able to find or afford these things in America. And anyway, that trip didn’t make them travelers, at least not the way the people I met at Stanford would speak of travel; that trip just made them immigrants, it made them charity. They became people to be saved, to be helped by institutions and individuals. I didn’t want to be saved, I wanted to be a member of the institution organizing the charity, the philanthropist dripping with generosity.

At one point, in the early years of living in New York, they became friends with another Chinese couple who showed them how to scavenge for edible food in dumpsters. This other couple was saving money to bring their little girl back from Shanghai, where they had sent her to live with her grandparents after a long struggle with their finances.

“Essentially, they were broke,” my mother told me. “They were irresponsible. They talked constantly about their little girl. I think her name was Christina. Every time we came across a carton of tangerines or something, the mother would say, ‘Our Christina only eats sour fruit.’ They were odd. They were the kind of people we didn’t know to stay away from back in the day. Just compare them to us. Your father was not only able to save up enough money on a student scholarship—a student scholarship!—to buy you a one-way ticket to America so we could be together, but he was also able to save so well that he could afford to gift me a real gold pendant necklace and you a keyboard because remember how in Shanghai when you were small, you said you wanted to play the piano?”

My mother made it all sound like a fairy tale and I didn’t want to point out that we were also separated for more than a year, when I was in Shanghai and my parents were in New York saving up enough money to reunite us.

“But,” my mother continued as if reading my mind, “it’s not the same as that family, you know. They were wild. They had so many problems. What kind of person can’t afford their own apartment after six years in America? What kind of person brings their child to America only to send her right back for a full year? And what were they doing to change their situation? Eating out of dumpsters? Selling chips from Atlantic City at an inflated rate to the elderly who didn’t know any better?”

“How long were you friends with them?” I asked my mother.

“Oh, you know how these things go. We would see them here and there and then they disappeared and we found out that they had gone to North Carolina to live with the woman’s brother. They came back with some unlikely plan to make money and then disappeared again for a few weeks and turned up with no mention of what happened to all that talk about starting up a tutoring business or whatever their idea was. That’s the kind of people they were. Show up out of nowhere and then disappear for weeks and then reappear. We fell out of touch. It wasn’t accidental. Eventually I think the man got a job in an office and it turned out that his wife was pregnant with their second child. We ran into a mutual friend a few years ago and they said that they live on Long Island now. New Hyde Park, which means they must have gotten it together. Anyway, it’s not important. All that’s important is what happens to our family. Our family is just too lucky. I’ve got you and your brother and your father and we live in this gorgeous house, and every day I wake up and feel so lucky.”

“Reel it in a little, Mom,” I said, rolling my eyes. I knew in the very fuzzy part of what I paid attention to that my parents had suffered, too, they had struggled, too, and whatever happened to them in the year before I was brought to America was somehow related to their refusal to ever order beverages at restaurants because paying an extra dollar or two for something they could get in bulk for cheaper activated some kind of trauma inside them. It really did. But even more astounding was how they never stopped me or my brother from ordering those drinks, though I rarely did anyway, because . . . because of what? Because I was closer to that time of their lives when they had suffered and lived without much energy to dream? Or was it because I didn’t like the sickly sweetness of regular sodas and preferred rarer drinks, like a tart, fresh- squeezed lemonade or a non-carbonated fruit punch with a bubble-gum aftertaste? I used to order those at Sizzler without even thinking in the days before my brother was born.

“You guys get one too,” I would implore them. “Let’s all get fruit punch.” But they insisted on the old tried and true formula: my father would order the steak dinner, which we would split three ways, and then my mother would get the salad bar buffet and I would get my fruit punch and all three of us would eat off the endless plates my mother brought back—mac and cheese and buffalo wings and fried chicken and spaghetti with meatballs and boiled string beans and broccoli and fried rice and rotisserie chicken breast and sometimes king crab legs if we were fast enough or lurked long enough and shrimp scampi and fillets of rubbery fish coiled inside of themselves on a mound of congealed buttery sauce. We would go through seven or eight plates of food and then rest for a bit or jump up and down to make room for round two, which was just as long but slightly less vigorous as we tackled another five or six plates of food. By the third round, we were slumped and sluggish with our belts undone, and then it was on to dessert. I would get vanilla soft serve with rainbow sprinkles then the swirl with no sprinkles and then chocolate with M&M’s and then a dozen chocolate chip cookies and one of each kind of cake—chocolate, butter- cream, carrot, red velvet, cookies and cream, pound, meringue, whatever. It all went inside and we burped the memories of the night for hours afterward. Sometimes we would wake up still full, our bellies round and the skin over them stretched tight like a drum. After my brother was born, we stopped going to Sizzler—he was too small and we were too greedy and too broke to tempt ourselves with any more nights out. The three of us had to look out for him first and each other second. At least, that was how we would have liked someone else to describe us—a pack, a unit.

But now I wanted to be free. I wanted to be free to be selfish and self-destructive and indulgent like the white girls at the high school my parents worked so hard to get me into, and once they did, once we moved into a neighborhood where no one hung out on the streets, where everyone was the same pasty shade of consumptive blotchy paleness, all it did was make me want to get away from my family. I envied white girls whose relationships with their parents were so abysmal that they could never disappoint them. I wanted white parents who didn’t care where I went or what I did, parents who encouraged me to leave home instead of guilting me into staying their kid forever.

The morning of my California trip, my mother kept bringing up how she didn’t leave home until she was thirty and even then it was only because my father was immigrating to the United States. “For a long time, I considered just not going.”

“Well, I’m not waiting until I’m thirty to leave home. You need to realize I don’t have the same life as you.”

At the airport, I avoided looking in her direction. It was bullshit that she made her sadness so known, and took up all the space my excitement should have filled. My family waited with me at the gate until the very last minute and then, as they walked me to the boarding line, my mother staggered and stopped in her tracks as if she had been stabbed and leaned against my father with the weakness of the dying. “Are you sure you want to go? It’s not too late to stay.”

“No,” my father said. “That’s not an option. Everything is going to happen exactly as we agreed. We want you to do well. We’re proud of you, okay? We’ll see you in three weeks.” My mother’s tears triggered a crying jag from my brother as well, and my father had to hold him back from running after me. It was strange to walk past them and wait in the back of the line to board the plane, knowing they were watching me go. I resisted looking back until there was only one person ahead of me in line. When I turned my head I saw the three of them huddled together—only my father was waving at me as my brother and my mother clung to him. It was a family formation that finally did not include me. I’m freeeeeeeeeeee, I thought as the agent scanned my ticket and then immediately began to panic when I realized I had missed my opportunity to say goodbye. I heard my brother shout out, “When’re you coming back, Jenny?” and then the door closed behind me and I hardly thought about them again for the next three weeks. It was only later, much, much, much later, that I understood and accepted that my parents paid for me to be free. All of it, I realized, had to be paid for by someone.

“You’ll drive a Mercedes, and I’ll drive a Porsche when we grow up,” he said to me while we sat on the curb waiting for the ice-cream truck.

“I can’t even freaking ride a bike,” I said, staring down the street, waiting to see if anything was coming.

On my ninth birthday, my mother was rushed to the hospital. Ten hours later, she gave birth to my brother. When we were both old enough to care, our mother told us that he was born at 10:22 in the morning.

“When was Jenny born?” my brother asked.

“Nine twenty-eight at night. But that was in China,” she reminded us. “It’s a twelve-hour time difference, plus you count an extra hour for daylight savings.”

“So?” we said.

“No,” our mother insisted. “You two were meant to be twins, but somehow you”—she pointed to my brother—“were stuck in my belly for an extra nine years. So lucky, you two.”

We rolled our eyes. “Whatever.”

When I got back from California, I was so tired from not sleeping for three weeks straight that two different flight attendants had to wake me up after the plane had landed and taxied. I slept straight through the car ride home and when we pulled up to our driveway, my brother tugged at my arm and asked if I would play with him.

“Now? I was going to go to sleep.”

“But it’s not even nighttime,” he said, his bottom lip quivering.

“He’s been waiting three weeks to play with you,” our mother said.

“Fine. Let’s play Monopoly. I’ll let you be the car.”

The next thing I knew it was four P.m. the following day and I was in my bed.

I cried out for my family and immediately the door swung open to reveal my brother had been waiting on the other side.

“What happened?” I asked him.

“We were playing Monopoly and you said you had to lie down for a minute and then you were asleep.”

“Why didn’t you wake me up?”

“I tried. I put water on you. And I set the timer to one minute and put it on your pillow next to your ear. I was blowing my breath into your nose and I tried to pull your eyes open but they kept closing.”

“And?”

“You kept sleeping,” he said, his voice breaking. “We only played for five minutes.”

“Oh,” I said, rubbing my eyes. “I’m sorry. I promise we can play tonight after I write an email to my friend, okay?”

“What about now?”

“I just said I have to do something first.”

“Okay, Jenny.”

The email took me hours and by the time I was done, it was too late to play Monopoly. I called my brother into my room so we could hang out before bed.

“Did you really miss me all that bad?”

“I cried every day. One time for three hours and twenty- two minutes,” he said, precise as usual. “I didn’t even have time to play.”

“Because you were crying so much? No way.”

“Yeah way.”

“What about the time you called me and all your friends were over playing baseball? You didn’t cry that time, did you?” “Yes.”

“Yes, you cried?”

“Yeah.”

I wanted to write another email to the boy with the pink button-down shirt who pulled me into his room one night when his roommate was out getting ice cream and took pictures of me. I missed California, missed the sweetness and newness of a boy, any boy, telling me cheeks were meant to be pink, and so I was meant to be in this world. But I was back in my old life now. I couldn’t even properly daydream without thinking about my brother crying alone while his friends were running around in our backyard. How did he do it? How did he find his way into everything? Even in my most private memories, the ones I told no one, sooner or later, he showed up, the perpetual invader, his small face asking me if maybe I’d watch him play a scary videogame and stand in front of the TV to block out the ghosts when they suddenly appeared.

My brother wanted to hook up his PlayStation to my TV on the one afternoon I actually had a friend from school coming over to watch three movies in six hours, so I picked up one of the videocassettes I had planned on watching and flung it across the room.

“You always do this. I have to spend every single day with you. Every freaking day and every freaking hour. I’m so sick of it.”

“So?” he said. “So what? I still get to play in here cause Mom said.”

“Mom said crap. Get out before I push you out.” He was sitting on the ground and I grabbed him by the ankles. He pulled little white curlies out of my carpet as I dragged him into the hallway.

“Never coming in,” I yelled after slamming the door against his outstretched palms. A second later, he was pushing his tiny hands through the wedge of space underneath my locked door. I took my slipper and whacked the tips of his fingers like he was a bug. I heard him crying on the other side. His fingers were touching my rug again. I took a glass of ice water from my desk and poured it all over his fingers. I heard the sound of my mother’s footsteps, thumping up the stairs from the basement den.

I threatened him, “I won’t stop until you stop.”

“I won’t stop first, I won’t stop first,” he repeated. I slumped down against the door and reached out a hand to stroke his little wet fingers, but they were gone. The footsteps stopped. I heard my mother scoop up my brother and knock on my door.

“Say sorry.”

I took my slipper and started hitting my own fingers as hard as I could.

“Say sorry,” my mother said, louder. “You can kill yourself if you want, but first you have to say sorry to your brother.”

I took my dictionary off the shelf and dropped it on the floor. “Don’t you dare,” my mother said, hitting her elbow against my door.

“Ye-yeah, ma-mom’s ga-going to punish y-you ma-ma- ma-ma-my Jenny.”

“One day”—I sighed—“you are going to have to stop missing me.” I pressed my chin against the spot on his head from where his hair swirled out. “Okay?”

“Why?” he asked me.

“You just have to get used to it.” A week ago, our father had gone to Cleveland for some work business. “How come you don’t miss Dad?”

“He’s coming back Friday.”

“So what? When I go away, I also come back. Why do you miss me and not Dad?” I wanted to shake the answer out of him. “Why do you miss me more? I want you to give me a really good answer or else I won’t ever stop asking you.”

“I don’t know. I just do.”

“Then I’m going to keep asking you. Why do you miss me but not Dad? Why do you miss me but not Mom? Why do you miss me but not anyone else?”

“I don’t know, Jenny.” He was crying now, and I shook my head.

“I’m not a nice person, am I? You ought to make me pay one day.”

“Okay,” he said, tears rolling down his face. “Then give me all your monies.”

“Okay.”

“I’ll buy you a Mercedes with some of it.”

Before dinner, I dabbed some of my mother’s lipstick on my lips. Tangleberry.

“Lemme kiss you on the cheek,” I said. I puckered my lips and moved in close.

“Are you wearing lipstick?” he asked me, arching his neck away from me. I had already pulled that joke on him three times that week.

“No,” I said, lightly pressing my lips to the back of my hand. “See? No lipstick.” I knelt down next to my brother and kissed his cheek hard enough to dimple it.

When we went to wash our hands in the bathroom, I remembered the mirrors and shielded his eyes with my hands as we were going in. “You’re my robot and I control everything you do!”

“Okay, Jenny,” he shouted back.

The summer after he finished second grade, there was a Saturday when we were inseparable for an afternoon, going around every room in the house arm in arm, which was hard to do because he was so little and only came up to my waist. I had to bend down really low, so low that it made my back ache but I didn’t care. We walked in circles, chanting, “We! Are! Best! Friends! We! Are! Best! Friends!” until our dad emerged from hanging up laundry in the basement and watched us with an empty laundry basket balanced against his hip. He shook his head and laughed.

“You’re both ridiculous. Come up here, I want to show you two jokers something.”

We walked up the stairs arm in arm, following our father down the hallway to my room.

“You see that hole?” he asked, pointing to my bedroom door.

“Yeah,” we said.

He took the laundry basket and hurled it through the hole in my door. There was room to spare.

“You”—he pointed at my brother—“kicked that in because you”—he pointed at me—“wouldn’t let him in.” He looked at us, arms crossed. “Two minutes later, you’re running around in circles saying you’re best friends? You should be jesters of the royal court.”

We were silent for a bit. And then we said, “So what’s your point?” For the rest of the afternoon, we went around arm in arm, still chanting, “We! Are! Best! Friends! And Dad! Is Such! An I-di-ot!”

Our mother came into my room when we were having a sleepover—my brother on the floor and me in front of the computer—and yelled very fiercely, “Go to sleep or never sleep in your sister’s room again.” I felt partially responsible because if it hadn’t been for me farting the entire chorus of “Row Row Row Your Boat” for my brother and making him laugh so hard that our mother heard it through the walls that separated my bedroom from hers, he would have never got- ten yelled at. I knelt down on the floor and asked him if he was okay.

“Are you thirsty? Hungry?” He nodded his head. “Be right back,” I said. “Don’t fall asleep.” I came back up with a turkey sandwich and a cup filled to the brim with water. While he ate I was reminded of the time when I had come back from a bad day at school and shut myself up in my room and watched taped reruns of Late Night with Conan O’Brien for three hours. When I realized I hadn’t heard any sounds from my brother in several hours, I went downstairs and found him sitting less than a foot from the television, watching Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and eating peanut butter with a plastic ice-cream scooper. Oh, I murmured when I looked inside the peanut butter jar: a hole right down the middle. Even now, I wondered if I had done right by him as I held out my hands below his chin to catch stray crumbs.

Whenever my brother and I start listing our grievances against each other—who wounded who more—my brother inevitably brings up the time I tried to kill him.

“You tried to kill me. Remember?”

“What? I never tried to kill you. That’s crazy.” But he swears that I did, that once, I asked him to take his plate of pizza downstairs and he wouldn’t, so I pinned him to the floor of his bedroom and held a knife up to his throat.

“It was probably a butter knife. You can’t even cut paper with those things.”

“No,” my brother insists. “It had sharp edges. You were going to kill me with a knife.” And it was true, he was right. I had been so angry that day because I made him a lunch of microwaved pizza, which I had cut into twelve neat little squares since he was so picky and only ate food that had already been pre-arranged into bite-sized pieces he could chew once and swallow immediately, and despite my having gone through the trouble of making a perfect meal for him, he didn’t show any gratitude at all. He refused to eat. I told him if he wasn’t going to eat it then he needed to put the plate of untouched food back in the refrigerator, but he refused to do that as well, so I took the knife I used to cut the pizza and held it up to his face. “You deserve to die. You make me want to kill you some- times. Maybe this time I will.”

It was an act of desperation. I should have told him, I would never hurt you. I would set fire to any tree harboring branches that might one day fall on your head, cut the arms off the first kid who tries to punch you in the face, pave down and smooth over the bumps on our street where you always trip, go into your nightmares and vanquish the beasts who chase you so you never ever have to be afraid. But what right did I have? When would I finally get it? That I was the one he needed to be protected from?

Once when we were napping side by side on our parents’ bed on one of the many afternoons we were left alone, I dreamt we were fighting on opposing sides of a civil war. When the war was over, I knelt down by my brother’s injured body and hacked him into four pieces. It was up to me to give him a proper funeral, but I had only two hands and couldn’t figure out which parts of him to carry back and bury and which parts to leave behind.

One winter, when I was home from college, I went outside in the dark, crossed the playground behind my house, and followed a narrow road up a hill. I forgot my glasses and for a while, I sat on a patch of grass, looking down at the town where I spent my adolescence, the town my family had moved to not long after my brother was born. The streetlights ap-peared as big as tangerines, blurry and orange. What I wanted was for someone to come looking for me, for someone to worry about me, for two adults to argue about me. I wanted everyone I knew and everyone I could know one day to wonder about me, to think of me as if I were the last Popsicle on earth, and oh no, before anyone got to eat me, I had already gone ahead and melted entirely! What I wanted was for someone to kneel down on the ground and lick the red sugary water of mememememememe curving and rolling down streets half-paved in asphalt. I worried about a world where my existence barely mattered. A world where I did not exist at all. Maybe that was the world I was headed to. Maybe that was the world I deserved.

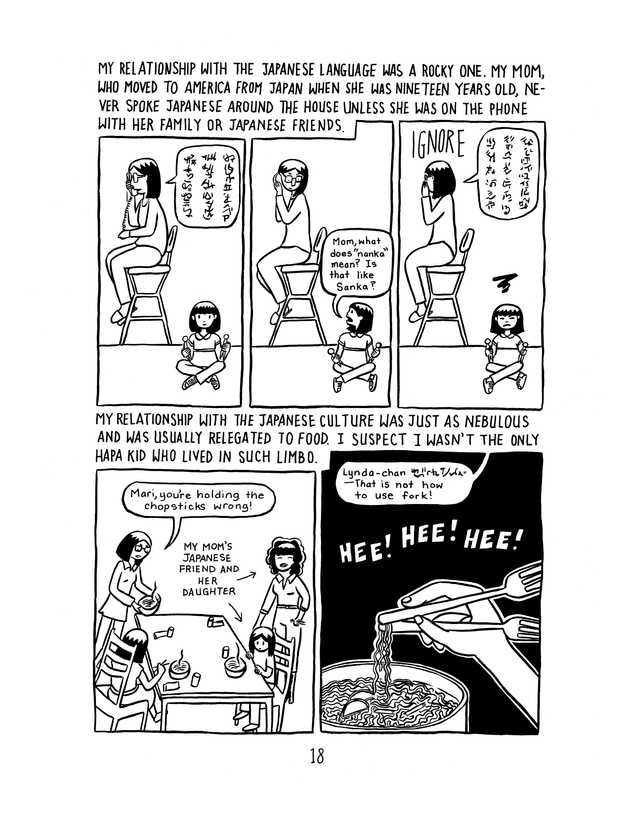

After a month of kindergarten, my brother still couldn’t write his name on a sheet of paper, and the teacher, Ms. Notice, was concerned and sent him home with a note.

“A notice from Ms. Notice,” I said, skipping around our living room, the happiest I’d been all day. He smiled when I ripped it up into four pieces, but pulled at my sleeve when I put one of them in my mouth. “You’ll die.”

“I won’t.” We worked on spelling his name for a good hour. “The letters go next to each other, retard,” I said.

“Ass.”

“What?” I looked at him in shock.

“What did you say?”

“Penis.”

I was tired. I felt on the brink of a deep, stirring sleep. “Let’s go outside and throw the ball around.” I took the pen from him and flung it across the room.

We went out in the lingering September heat. I threw the ball up and neither of us caught it. Then my brother picked up the ball and threw it into the tree. It was stuck up there. “You’re good at throwing. I’ve never seen a ball go so high.”

“I know,” he said.

I wanted to hug him, to kiss his cheek until it was sore, but I knew he was getting older. He would protest, he would one day no longer hug his arms around my legs because he was short, or make a fist around my pinky when I picked him up from school, or crawl into my bed with his wet hair and face, no longer say it hurts me to leave you before going to his friend’s house, or I missed you all day after coming back, be-cause he would get old, and I would get even older. Maybe we would grow apart, he would develop a personality that I would know nothing about, we would start our families, have children of our own, and there would come a point when in thinking about “family” we would think of the ones we made, not the ones we were from. From that point on, I would refer to him as “your uncle” and he would mostly refer to me as “your aunt” and it would take a long time for our children to even understand that we were siblings first, but more than that, our children, just as we hadn’t, would likely not think much about a time before they were born, a time when he was my brother and I was his sister, and together, we were our parents’ children.

II.

The year I moved out to California for college, we talked on the phone every week. It was hard to hear him through all the tears in the beginning. Then it was every other week, and by the time I was a senior, our mother had to order him to stay on the phone for at least five minutes a month.

“Do you miss me?” I asked him during one of our recent five minutes.

“Yeah, kinda, but sometimes I forget about you.”

“I would never forget about you.”

“Do you want to talk to Mom?”

Now I had to learn about him from my mother. Last week, she reported over the phone, he ate a penny. “Total freak thing,” she said.

“Let me talk to him,” I said.

“Hold on, I just have to check if I have any money in my wallet.”

“Why?”

“Your dad and I have started giving him a few bucks to talk to you.”

“Fucking fantastic.”

When he was five, he told me he had put his finger down his throat and accidentally threw up a bit. “But, I swallowed most of it back down,” he had said at the time.

“You only did it the one time, right?”

“I did it other times too.”

“How many other times? Two? Three?”

“Fifty to sixty.”

“Holy shit. I don’t get it. Do you not like the way your body looks or something?”

“I just wanted to see what would happen if I put my finger down there.”

“You know what happens—you throw up, develop an eating disorder, and then you die.”

“You can die from that?”

“From making yourself vomit every day? Oh, for sure.”

“No, from putting your finger down your throat? What if you die right after doing it?” “What is with you? Stop putting your finger down your throat, dude.”

“Get this,” I told my friends at school the next day. “My five-year-old brother has an eating disorder. How is that even possible?”

When my brother was starting third grade and I was starting senior year of high school, our grandparents came and lived with us in New York for six months and brought an elec- tric bug racket from China with a tag attached that had a skull and crossbones above big bold letters: watCH out! eLeCtroCutes ProbabLe.

“What the heck are electrocutes?” my brother asked me.

“Oh, it’s a typo. It means you could get electrocuted if you touch the racket when it’s on. So, don’t touch it, okay?”

“Never,” our mother said, popping her head into my brother’s room. “Never never never never never never never ever touch.”

“Okay, okay,” my brother and I said. “We get it. Can you please get out?”

But my brother was haunted by the racket. He rolled up pieces of paper and pressed the tips against the racket.

“I saw sparks,” he told me later.

“Seriously, stop obsessing. Leave it alone, okay?”

But he couldn’t. He wanted to put his finger on the racket.

He said his friend Harrison touched his lips to the racket and had to wear a bandage over his mouth for a month. All the parents we knew were calling up their parents in China to tell them to stop bringing over the electric rackets. “Do you want your grandchildren to have lips or not?” I heard my mother asking my grandmother in the kitchen one evening.

“I touched it,” my brother told me the same week his friend Harrison burned off his lips.

“Oh my God. Why?”

“I just did it for a second, to see what would happen. For some reason my brain is telling me to touch it again. What happens if I put my mouth on it?”

I took the batteries out of the racket and tossed them into a pile of logs in our backyard. The year after that, I went away to college, and in my extended absence, my brother found the electric racket hidden behind a suitcase in the basement. He told our parents to get rid of it permanently, and they laughed and called me on the phone and said, “Your brother is still our little sweet baby. He’s just trying to get attention, you know?” To that I said, “Please. Please pay attention to him, then,” and to that my mother said, “Of course I’m paying at-tention. You think I just ignore him?” and to that I said, “Why do you always call me when I’m trying to study? Every minute I talk to you is one point less on my midterm next week.”

Several years after my brother tried to burn his lips on an electric bug racket, and many years after I accidentally burned my brother’s hair with a candle, I found out he would sometimes light a candle and wave his index finger back and forth through the flame. Sometimes, he would hold a knife up to his own throat and inch it along the growing hairs on his neck, daring himself to get close enough to draw blood. He would swing his keychain near his mouth, letting the key graze his lips. He would dip the key into the back of his throat until he gagged before yanking it back up. “I just wanted to see what would happen,” he said to me on the phone, again and again and again. “I kept thinking, What if I swallowed the key? What if the knife pierced my skin?”

“What if,” I said. “What if you start wondering what would happen if you jumped off a bridge? What if you start wondering what would happen if you held a loaded gun to your head? What if you die trying to figure out what if? Then what? Then you’re dead.”

After my brother ate the penny, he called our mother at work and told her that he had eaten something he wasn’t supposed to and that his stomach felt weird and he wanted to go to the hospital. She rushed home, weaved through traffic on the LIE, and drove my brother to the emergency room, where, behind partially closed curtains, a doctor with a glass eye put his finger up my brother’s butt and said, “You have some hard stools lodged up there. Other than that, everything’s fine. But tell me something. You’re thirteen years old. Most of the kids who do this kind of thing, eating pennies and quarters and tree bark and tacks and Happy Meal toys—you name it and I’ve seen it—most of the kids doing things like this are four and five years old. You’re thirteen. Don’t you know better?”

“Did it make you feel bad?” I asked my brother on the phone after our mother bribed him with a twenty to talk to me.

“No,” he said. “I didn’t care that the doctor put his finger up my butt.”

“No, not that. I mean when the doctor said the thing about you being too old to eat pennies.”

“I wasn’t eating pennies.”

“Swallowing, whatever. Did it make you feel weird when the doctor said the thing about you being too old to do this kind of thing?”

“I guess. Dunno.”

“Why did you eat the penny in the first place?”

“Not eat, swallow.”

“Whatever. Stop being so specific about everything. Stop correcting. Why did you try to swallow the penny in the first place?”

“Uh-un-uh,” he responded, his shortcut for I dunno. “The thought just came into my mind. I kept thinking, What if I swallowed a penny? What if it got stuck in my throat? Would I die from a stuck penny? I was thinking it so much I couldn’t sleep. I figured, instead of wondering what if, I should just do it. I’m not stupid. I just wanted to know.”

“But you can’t know. And if you die from these experiments, you still won’t know. You’ll be dead. Dead people don’t know because they’re dead. Are you depressed or something? You can tell me. It’s okay to be depressed. I can help you.”

“No,” he said. “It’s not that. I just can’t stop wondering, What if?”

“It’s perfectly normal to be depressed at your age. I mean, look at how I was. A complete fucking nightmare of a human being. Do you remember how I would just shut myself up in my room and sob over nothing?”

“True. You were an extremely difficult teenager,” my mother said. “So listen, your brother went to play video- games. He said his five minutes were up.”

“Can’t you give him more money?”

“No. Not right now. He has too much to do.”

“You just said he went up to play videogames.”

“What are you having for dinner tonight? Anything yummy?”

“I don’t know,” I said, petulant. “Pennies stir-fried with garlic.”

He was three and I was twelve when our parents bought our house in Glen Cove. We had successfully done something people studied in academic textbooks—we became upwardly mobile. We moved from our mostly working-class Puerto Rican and Korean neighborhood in Queens to a named community (its namesake was J. P. Morgan, the very tycoon my father worked twelve hours a day for, the reason why we never ever saw him) in a mostly upper-middle-class white neighborhood on Long Island. Everywhere we went and looked there was unused space, there was room for two people to never have to touch each other or breathe in the same approximate air. There was silence to fill, grass that had never been trampled on, trees with undisturbed spiderwebs. Between the ages of twelve and seventeen, I was the first person to come back to the house on weekday afternoons. I had about forty-five minutes to myself before my brother came home, five hours until I had to cover up everything that went on in our house before our mother returned from work, and eight or nine or ten hours before our father came home and checked in on us. We would wait up for him in our pajamas, having done everything we needed to do that day besides see him. Sometimes if I was in a selfish mood, I’d pretend to be asleep in my bed to avoid the five or so minutes I had with my father at the end of the day—it wasn’t like I was ever going to know him this way. But still, adding another day to the stack of days I missed out on knowing my father was immense and weighed on me like a millstone in a fairy tale. In a way, we were in a fairy tale—all those hours my brother and I spent alone in an empty house together, and all the times I tried to get my brother to believe that our parents had died, that I had just gotten off the phone with a police officer who found them mangled and lifeless, covered in the bloody shrapnel of a massive car wreck.

“It’s just you and me now,” I would say to him. “Who do you think is going to take care of us?”

“Our aunt and uncle will,” my brother would sob. “We’ll go to China and live with Grandma and Grandpa.”

“No can do. They already said they won’t take us. It’s in the will. If Mom and Dad die, we’re on our own.”

We were already on our own. We lived in a split-level house with windows on every level, sliding French doors in the kitchen that led out to a small deck, two skylights and floor-to-ceiling windows in the living room, four sets of windows in the family room, two windows in each bedroom. We were told to keep all the blinds tightly shut and all the curtains closed. “So that no one knows you’re home alone,” our mother explained. Sometimes though, I would pull up the blinds anyway. I would draw the curtains and let in the light from outside. So what if we were seen? So what if our secret was revealed? What did I care if someone saw me at home, eating cake and drinking coffee, heating up frozen pizza in the microwave and cutting it into bite-sized pieces for my brother? Why shouldn’t someone have seen me holding up a fireplace poker high in the air, aimed at my brother’s forehead for no other reason except that he annoyed me, when all he had to defend himself against me was a useless plastic bat—why shouldn’t someone have seen and intervened? I had never been a worse adult than when I was still a kid.

“Will they take us away,” my brother asked our parents, “if they see us?”

“Yes, they will,” our mother said.

“Jenny,” my brother said, pleading with me one of the afternoons when I told him that our parents had died in a car accident. He was pulling on my arm to stop me from drawing up the blinds. “We can’t let anyone see us.”

“You stupid idiot,” I said. “Everyone already knows.”

III.

I am home this week, visiting my family before I go back to my life in California. As soon as I enter the front door, I remember my old self—restless, moody, lonely, rageful. When I go through my closet, I find my old laptop from high school that my brother would use from time to time, afternoons when he wanted to be near me but I didn’t feel like interacting with him so I would give him my laptop. There weren’t any computer games installed. He mostly drew pictures on Microsoft Paint that he tried to show me but I always said, “Later, when I have time.” After I went away to college, he used my laptop a few more times to write poems for school. One of them was about me and he read it out loud over the phone:

“I have a sister Once she chased me with a big metal thing. I found a yellow plastic bat And I fought back with courage!”

“So did you win the poetry contest?”

“No, the kid who wrote about his grandmother who survived the Holocaust did.”

“Seems rigged,” I said.

“It’s not.”

I look at the poem again and then go through some other files, including one called “Fight on Dirt,” a painting of magenta, lime-green, and teal-blue stick figures on brown mud. I see another file named “Power Rain,” which I remember seeing a long time ago but never opened. I wondered briefly back then what “power rain” was—massive droplets of rain, each one fat enough to contain an armed soldier ready for combat, hitting the ground, causing tremors in the earth?

I open up the file and realize the full name is actually “Power Rain Jurs.” Sour tears well up in my eyes and fall into my mouth. I feel self-conscious and stupid crying for myself— for my shame, for my regrets, for how quickly a childhood happens. I wish I had acted better. I wish I had been the kind of sister who was patient enough to show my brother the proper spelling for “Power Rangers.”

Whenever I’m home for a few days, I start to feel this despair at being back in the place where I had spent so many afternoons dreaming of getting away, so many late nights fantasizing about who I would be once I was allowed to be someone apart from my family, once I was free to commit mistakes on my own. How strange it is to return to a place where my childish notions of freedom are everywhere to be found—in my journals and my doodles and the corners of the room where I sat fuming for hours, counting down the days until I could leave this place and start my real life. But now that trying to become someone on my own is no longer something to dream about but just my ever-present reality, now that my former conviction that I had been burdened with the responsibility of taking care of this household has been revealed to be untrue, that all along, my responsibilities had been negligible, illusory even, that all along, our parents had been the ones watching over us—me and my brother—and now that I am on my own, the days of resenting my parents for loving me too much and my brother for needing me too intensely have been replaced with the days of feeling bewildered by the prospect of finding some other identity besides “daughter” or “sister.” It turns out that this, too, is terrifying, all of it is terrifying. Being someone is terrifying. I long to come home, but now, I will always come home to my family as a visitor, and that weighs on me, reverts me back into the teenager I was, but instead of insisting that I want everyone to leave me alone, what I want now is for someone to beg me to stay. Me again. Mememememememe.

I burst into my brother’s room without knocking and he’s playing a game on the computer with such concentration that I can’t get him to look at me even as I’m pulling the swivel chair he’s sitting on away from his desk.

“Stop,” he says. “What are you, an animal?”

“Remember the time I burned your hair and it smelled like popcorn?”

“Yeah, so? Why do you always talk about that?”

“It’s funny to me.”

“It’s stuff that happened when I was little.”

“You look so old now,” I say. “You’re going to be taller than Dad.”

“Knock next time,” he says. “You always just barge in.” “Well, that’s what you always did when you were little and I let you do it so many times. Don’t you owe it to me to let me barge in a few times?”

“That was then.”

“Well, this will be then one day too.”

“That makes no sense.”

“That’s because sense isn’t made, it’s learned.” “Yo, you really need to get out of my room.”

At night, when everyone is sleeping, I sneak into his room like I used to when he was little. There were nights when I missed him, when I stayed up too late on my own after insisting that he couldn’t sleep in my bed with me, after insisting that he had to learn to sleep multiple consecutive nights in his own bed, nights when I stayed up trying to be my most romantic self, when I stared at myself in my bedroom mirror, flirting with myself, seducing myself, laughing at my own jokes, playacting the kinds of friendships I fantasized about having once I was no longer in this house. On those nights, there would often come a moment when I suddenly missed my brother so much that it was physically unbearable and I would creep into his room and watch him sleep, his little chest and his little face and his little knees smashed up against the mesh barrier that my parents installed so he wouldn’t roll off his bed. My brother never slept in the center of anything—he was always against some barrier.

I’d kneel down next to him and kiss his pillowy cheeks or run my finger across his long, curled eyelashes that looked so angelic and heavy when wet. I’d stroke his hair from the little swirl in the center of the top of his head where it all seemed to originate. I’d take his fingers and wrap them around my pinky. I wanted him to wake up and hang out with me and when he wouldn’t, I’d pull his eyelids back and reveal the whites of his sleeping eyeballs. “Can you see me?” I’d clap my hands loudly next to his ear. Sometimes I’d pull him up like he was a marionette and I was his puppeteer. Through all of it, he would just sleep and sleep and sleep, even the few times when I dragged him fully out of bed and made him stand up- right on his tippy toes, and when that wasn’t enough to wake him up, I grabbed his shoulders and made him do jumping jacks by pulling his arms up over his head and then letting them slap down hard against his legs. One time, he opened his eyes, though even then, he didn’t remember seeing me the next morning. There was no way to stir him.

For years after I went away to college, he was afraid to sleep on his own. The first few months, he slept in my bed, but once our mother insisted on washing the sheets and pillows, he was no longer comforted by it. He slept in our parents’ bed after that for a little while, and then when he was too old to sleep with them but still too scared to sleep alone, they hid a twin-sized mattress on the floor next to their bed. It was positioned in such a way that anyone who peeked into our parents’ bedroom would not see it.

“It’s on the floor,” my mother said, “so he can’t fall on the floor! It’s been working out great.”

“You always want a baby in the house,” I accused my mother the year he started middle school. “You don’t even know who you are without a baby, do you?”

“And you,” she said, “don’t know anything.”

Last year, I helped my dad take the mattress into the garage and cover it with plastic.

“Are you crying?” I looked at my mother and then looked away.

“You could have just left it there,” she said to my father. “It’s his choice if he wants to sleep there or not. And now he doesn’t even have the choice.”

Even though I tried to distance myself, I felt complicit in her tears. I didn’t want my brother to grow up either, just like my mother hadn’t wanted me to grow up nine years ago. I was the same as her—someone who nurtured my pain as if it could stop things from changing. No matter how many times I saw my mother’s watery eyes in my doorframe the summer before I left for college, it wasn’t enough to stop what had been put in motion: that I was leaving home and I wasn’t going to wait until thirty to do it.

Next year my brother will be in high school and when I was in high school, I had a kid brother who grabbed my leg and walked with it in his arms through our house when it was cold, sat on my shoulders when it was hot to get closer to the ceiling fan, and slept in my bed when he missed me, which was all the time. I kneel down by his bed and kiss him on the cheek, no longer the pillow cheeks I remember from years ago, but now bonier and dotted here and there with pimples. I hold his hand up like he is my king and I am his loyal servant, and I kiss it, bring it up to my heart, hold it there for a moment, and say, “With all my regard.” I don’t let go of his hand right away. “Don’t forget me.” He stirs, and I wonder, for the first time, why it should be so important that he remembers me, that he remembers all of it? “Or forget me,” I add, placing his hand back underneath the blanket. “Or for- get some of it. Or remember me. Whatever. It’s your life.”

I leave twenty dollars on his desk to secure time for our next phone call. I want it to be possible for us to share a home again but I’ll be gone from this house in a week, and he will maybe tell our mom about a dream he had where he was swat- ting this giant bee away from his cheek, and finally, it came right for him, and no matter how much he ducked or swung his head, the bee remained close, and when it finally stung him, it was a soft puff, not bad at all, and then, it was on to the next dream.

SOUR HEART by Jenny Zhang

Copyright © 2017 by Jenny Zhang

Published by arrangement with Lenny, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.